marbles, a magic circle, savages and Texas

a story about a goddess and the twilight of the dusty Southwest

Back then, my barrio was my land to roam. Most of it was rock, polvo and stickers, and they know my feet well. Fireflies hummed by me and called me by name. The night was waking up. The twilight was breathing life all around me. I sat on chalky earth waiting for my grandmother. I had gathered some twigs and tried to light a fire for her, a Queen of my lands, nothing less would do—but a breeze blew out my last match. I had chosen the place where my fires often sang, but on that night it was the Moon that shined over me. It was waiting to shimmer on everything. The sun kept fading. I sat there. She was going to teach me something. Canícas she called it.

Moments earlier I had gotten caught in the forbidden chest, the one I was not allowed inside unless my uncles allowed. That chest, full of oddities and curious things I had never seen before.

Except this time I wasn’t scolded. In my hand I had a bag of glass stones with markings, they looked runic to me. I would stare at them through the sun in secret—holding the bag tight so as not to make noise. Out of all the curious things in there, the glassy stones drew me. They felt magical in my hand, I liked the weight.

—“¿Quieres aprender?”

Startled, grandma quietly standing behind me. I look at the bag and I say “¿aprender qué, ma?”

I’m not in trouble?

“¡A jugar canícas!” she tells me. I feel butterflies. She tells me to go outside before it gets too dark, and to find a place for us, she’ll meet me there.

I remember the pulsing of the ground I sat on. It felt powerful that night. Something was different.

Do you want to hear the rest of this story?

I hope it reaches those that find magic in life still. Let me first give you context, where it sits in my heart. In my bones. Things that were born from exile and ancestral struggle.

in Táyshaʼ where I played in the dust and thorny grass of my exiled ancestors

I don’t remember being born. Some people say they remember that. I imagine maybe it felt traumatic, very cold and loud. I do recall my life in Táyshaʼ however, and what parts of her I kept with me down to this day. That’s the part of being born I remember. The parts I can still tell.

Táyshaʼ during those days had magic that was raw, instinctual and present. I was born into the barrio and a tiny plot of land made of hard stone and chalky polvo. Arid, and if you had the water for it maybe a patch of grass. Either way, you will have chancaquías anywhere you step. Up close these stickers look like horned goats to me. This is the land I was born into. I will always remember El Rio Grande. That water knows the voice of our family, it knows my skin and it knows my fear.

This is the pueblo that also gave us many natural springs that I tasted, especially from the hose. The same springs that colonizers took and used to develop the town I was born in, San Felipe del Rio.

about The People of this land that walked on it long before I did

The colonizers called the land Tejas because they kept hearing the people use the word táyshaʼ which meant friend. The Spanish couldn’t say shh so they changed it to Tejas. Later, the American colonizers would change it to Texas and then drive my People out further into a nomadic life toward Mexico. The Kikapú originated from the Great Lakes after all.

The Kikapú were one of the last to resist assimilation and I keep that same spirit alive to this day.

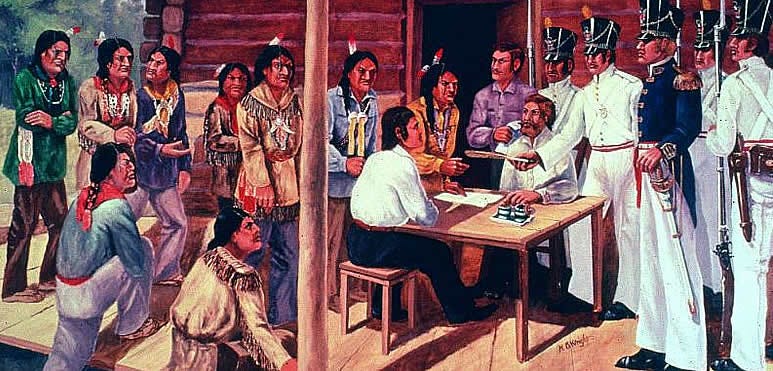

However, the land was eventually stolen, pieced out like a good hunt, but done so greedily there was no room for others to also prosper. All of it was stolen with a pen and a gun.

The very land I grew up in has deep history for my ancestors. A lot of roots and magic exists there for us. Those lands still carry the bones of our generations. I can trace my blood to the place my grandmother was born. A Kikapú city Múzquiz, in Coahuila, Mexico. The place where her tribal lineage became severed due to poverty.

When I was a child I was taken to Múzquiz, I was there on that land. I ran barefooted on that land. The land our people were pushed in and out of in the early 1900s, it’s still there to tell its stories through magic.

a prince with the bones of a queen

I lived with my grandparents for a time. As a child I had a lot of freedom. I was well behaved. Matches in my pocket, no problem. At that time the barrio used to call me El Principe. The Prince. My grandmother gave me that title. Prince of what? I wasn’t sure yet but the barrio was my home.

It was through my grandmother I experienced many things for the first time. My first dress. My first smoke. My first many things. Including the magic I witnessed one twilight. That hour never left me.

living with my abuelos, the fragments and racism

For a while it was just me and my grandparents. My mom and my dad were traveling looking for work. For a period of time, they worked in the onion fields, like my grandparents who had picked potatoes and traveled wherever the work was, places where they would hire “wetbacks.” We all have many experiences dealing with racism, but it is all part of our ancestral struggle.

In spite of all this I was given a magical memory. It’s time to tell it.

My grandmother calls out to me and says, “¡ahí voy!” She’s ready.

There’s those butterflies again.

all her magic was in the rhythm of her walk and the intent of her finger

The polvo. Dust. Stoney ground.

Out of the shadows of rosebushes, a banana tree and the orange glow of the front door, she appears. Her gown is light, but the pattern has colors. Her colors. She’s barefoot.

Her feet get closer. She greets me but I hear it faintly. I feel her steps. I see the polvo puff up on every beat under her. Her gown, just above her ankles.

“¿Listo?” Ready?

I cross my legs and sit up. She sits opposite to me. Butterflies. The moon’s sheen, bluish on the fading shadows. She sees my attempt at a fire and says nothing. Her hand comes forward, I follow her finger, it meets the earth. She begins to draw a circle, the polvo rises up around her finger. It’s just like when she walked.

She reaches for the bag of magic glass and pours it into the circle. Glassy eyes open and gleam up at us. Butterflies.

I swallow. My breathing careful.

“Este es El Canicón.” She brings a larger steel marble up to my eyes. She lets me hold it, it’s heavier than the others. It feels respected. It feels like its purpose went far beyond a game. Like it used to be something else. It carried heavy memories. I gave it back.

She explains what El Canicón’s purpose is, and shows me its power. She places her thumb under her pointer and charges tension. She casts the stone and I see eyes scatter into starry galaxies. Some of them go beyond the orbit’s threshold. Beyond the line of a goddess.

She keeps those as her bounty.

Loved the storytelling from you. Such beautiful descriptions and reverence for your grandmother. I hope to read more along these lines as time goes on 😌